On being human

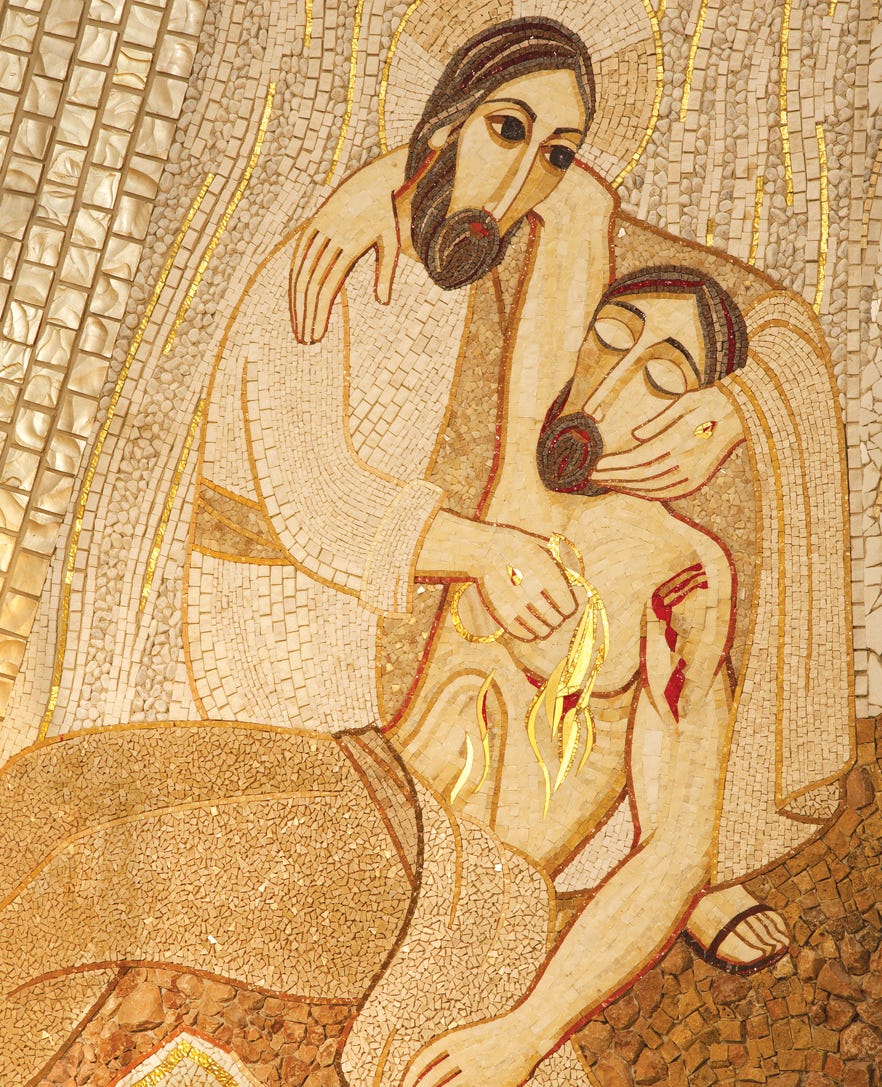

The Good Samaritan and being human, together

“There must be more to life than having everything!”

-Maurice Sendak, creator of Where the Wild Things Are

What does it mean to be human? What’s it for? What are its defining characteristics? How do we define this thing that we both are, and aspire to be?

Can you mis-spend it? Can you do it wrong?

Only humans – as far as we know – would do something like “wonder what it means to be human.” Cats don’t wonder what it means to be cats, and dogs certainly don’t. They just do it. But humans are different: We can examine and ruminate and make choices. And our choices, for better or worse, tend to be a good deal more consequential for the creatures around us, let alone for the planet, let alone for ourselves, than a cat’s or a dog’s. When humans have a shift in their sense of what humanity is for, they can go from caring for the world to burning it down, all in the name of “the markets” or whatever. I’ve never seen a cat do that.

So we should talk about what it means to be human. And I want to talk, using some of the tools common to Christianity. I want to talk about being human, as a Christian speaking to other Christians. Not because I think of myself as a Christian any more, in any dogmatic sense. I don’t. But rather, because I want to be able to speak the language of Christianity, at a time when Christians in the West have very demonstrably lost their way. If Trump and Elon are America’s messiahs now (and apparently to some in Canada, too!), despite that neither of these man look nor act anything like the homeless, misunderstood, abused, suffering-and-crucified-in-the-name-of-self-giving-love Jesus, then the Church’s delusions are out of control. Christianity’s sickness has at last visibly eclipsed its capacity to read its own traditions. It has become its own much-anticipated ‘antichrist’.

I was reading this week an interview between David Brooks and the theologian Dr. Luke Bretherton, over at Comment Magazine. Credit where credit’s due, I really appreciated the interview for its thoughtfulness and for Bretherton’s exegesis of a number of bits of the New Testament. Including the story of the Good Samaritan, which inspired this post.

For those not familiar (but who are willing to read this anyway – and if that’s you, thank you), the Good Samaritan is a parable, in the Bible, told by Jesus, in chapter 10 of the Gospel of Luke. It’s a parable told by Jesus, meaning it’s a story told by a character in a story. Which is an interesting way for the Gospel of Luke to go about trying to make a point. But whatever; the parable of the Good Samaritan is one of these stories that Jesus, in his story, tells.

And it’s pretty well known; maybe you know the gist of it, even if you’ve never read it. A man is walking the road between Jerusalem and Jericho and he gets mugged. He’s beaten, he’s robbed and stripped, and he’s left for dead. Three people happen upon him in his moment of need (because it always happen in threes): First comes a priest. Then comes a… let’s call them a life-long religious worker (in the story it’s a Levite). And then finally the titular Samaritan.

Both the priest and the Levite are religious people and so might be expected to help a traveler who’s been badly beaten and robbed. But in the story they don’t; they keep to themselves, they stay as far away from the man as they can, and they pass him by. Then comes the Samaritan. Now, contextually (because, don’t forget, the New Testament wasn’t written in English in the 1950s; it was written in Greek, two thousand years ago), it’s important to remember that the ancient Jews of the 1st-century, Judea, and the Samaritans didn’t get along. The Samaritan in this story is an enemy to the man dying on the side of the road, by virtue of his culture and his ethnicity and his religion.

But he stops anyway, and he helps. He takes the beaten man away to be cared for. More specifically, he pays for it! Such that, as Bretherton puts it:

“The Samaritan is depicted in the story as the truly human one. His humanity is revealed at the point of encounter and how he responds. His response is simultaneously a gesture of enemy love, help to one suffering, and friendship. It contrasts with those who think, ‘Don’t touch, stay away, protect yourself,’ and so pass on by and thereby deny not only the humanity of the one robbed and beaten but also their own humanity.”

Now, there’s a great deal more that could be said about this. But I think it’s particularly important to recognize that denying each other’s humanity by turning away from others in their need — for Bretherton and for the story of the Good Samaritan as well, this is to deny our own humanity. And beyond that is the fact that this story is not an aberration when you’re reading about Jesus in the New Testament. He tells stories like this all the time. And he lives it out: He has a noted habit of hanging out with people with chronic diseases (which had religious and even moral implications in the world in which the story is set). And sex workers. And other unsavory characters (like, was one of the disciples a “terrorist”? ).

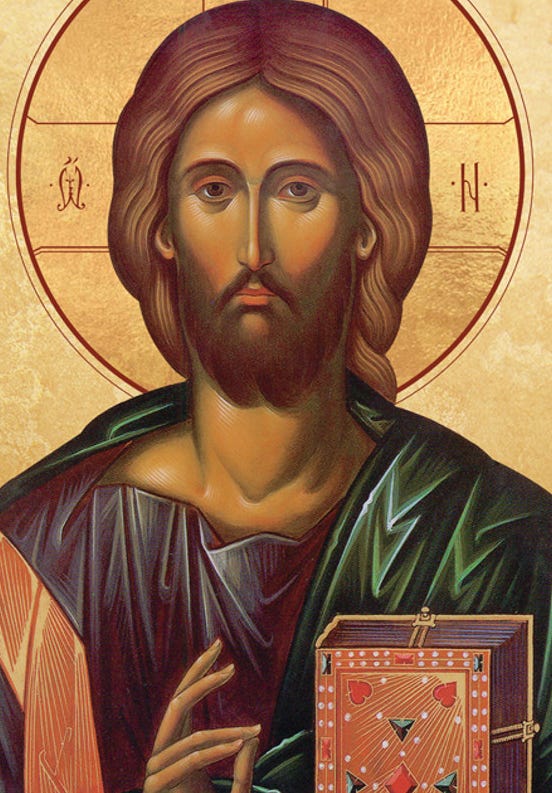

My point is this: Christ’s humanity — the Christian answer to the question, “What does it mean to be human?” — is over and over again in the Gospels a humanity shaped by self-sacrifice and love for the other. So much so that Jesus commands his disciples to ‘go and do likewise’. I agree with Bretherton that humanity needs a horizon to look up to, a transcendent something that we aspire towards, that helps push us beyond just being the selfish, tribal, myopic, Machiavellian little monsters that we can often be. In the story of Jesus, Christ’s humanity is in conversation — we might say its in a complimentary relationship of sorts — with his transcendence, with his divinity. His humanity has something it’s being contextualized and ‘called upwards’ by. That could be a whole post unto itself.

But that context is the one in which the Gospels describe true humanity by describing Jesus and telling his story. Because Jesus, as well as being ‘Son of God’ in the New Testament, is also “Son of Man,” or “the human of humans.” And that human is one who not only willingly suffers himself, but who also willingly enters into relationship with the suffering and rejected in his world.

I don’t see that when I look out at Christianity in our world, and I wish I did. I hope that there are individual communities still leaning hard into that call. But as a movement, I don’t think Christianity (for the most part) even remembers what kind of humans Christ asked them to be.

So if you’re a Christian, my question is this: What kind of human do you believe you’re supposed to be? How would you describe it? And how do you imagine the way that kind of human should relate to others, or to the planet, or even to your own self?

And if you’re not a Christian, my question is similar: What kind of human do you think you’re supposed to be? And why do you think that? What is it that tugs at you to not just be a selfish, live-for-yourself black hole of wants and impulses, but rather to be a person that makes the world a bit better for having lived in it?

Be well, friends. And thanks for reading.